Soup Dumplings, Fish Wontons & Eating the Season in Shanghai

What I ate (and loved) in the Chinese megacity

If you’d asked me 15 years ago, I wouldn’t have picked Shanghai as my food destination in China. I probably would’ve laughed and stayed loyal to the bolder, spicier dishes of Sichuan. Shanghai food? Too sweet. They even put sugar in tomato and egg stir-fry.

But my curiosity and appreciation have grown for food I didn’t grow up with. It’s also undeniable that Shanghai offers an ever-evolving and exciting food scene: time-honored local specialties, perhaps the most complete collection of regional Chinese cuisines, plus international and creative fusion kitchens. It’s a city of contrasts, where you can find street food for one or two euros or indulge in luxurious fine dining, reflecting the city’s wealth divide. The internet even jokes about a separate currency, “hubi,” to describe Shanghai’s crazy pricing. In the French Concession, with streets lined with English and French signs, I sometimes feel like I’m strolling through Berlin. But just a few blocks away, baos are steaming and scallion pancakes are sizzling for busy commuters.

Shanghai cuisine—even its street food—doesn’t make the cut for the Eight Great Cuisines of China, but it’s heavily influenced by the surrounding culinary powerhouses, which are on the list: Anhui, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu. You’ll also find traces of other regional cuisines and even Western influence, forming a unique subgenre called Haipai cuisine, with localized borscht and schnitzel on the menu.

I visited the city in late 2019, again in spring 2023, and now in 2025. This time, I focused on eating as locally as possible. As someone who didn’t grow up with this cuisine, the meals gave me a solid and much-needed introduction.

Xiaolongbao 小笼包

Steamed soup dumplings—xiaolongbao—are probably the first thing that comes to mind when people think of Shanghai street food. Locally, they’re called xiaolong, xiaolong mantou, or tangbao. I had half a dozen places bookmarked just for this one dish.

I ended up at Jiajia Tangbao (佳家汤包), just around the corner from our hotel on Huanghe Road—recently made famous by Wong Kar-wai’s latest TV show. It was already packed at noon, but we quickly found a shared table with two young women. One corner of the room displayed a large calligraphy sign reading “Shanghai Tangbao,” while the other featured a see-through kitchen, where skilled chefs folded dumplings at lightning speed—each bun shaped in seconds by their dancing fingers.

We ordered a trio of fillings: classic pure pork, pork with crab, and pork with shiitake mushrooms, plus a simple egg and seaweed soup. The bamboo steamer arrived about ten minutes later, and we devoured the dumplings quickly. These were some of the best soup dumplings I’ve had. The skin was thin but sturdy, the filling well-seasoned, and the broth pleasantly hot—not mouth-burning. My favorite was the pork with crab: xiefen, 蟹粉 (a mix of crab meat and roe), which added a natural sweetness and umami that didn’t overwhelm. Already excellent on its own, but for balance, a dip in seasoned vinegar and shredded ginger adds a nice sharpness.

Another spot I visited in 2023 was Lailai Xiaolong (莱莱小笼), known for its crab xiaolongbao and higher price point. It’s now an internet-famous destination with a reliable line out the door. Their pure crab version came individually plated, flatter and chubbier than usual, with a higher soup-to-filling ratio. Rich, creamy, and bursting with umami, yet not fishy. They run their own crab processing facility outside of Shanghai, where the meat and roe are picked, cooked, and delivered fresh daily. For the true crab roe enthusiasts, there’s even a pure roe version.

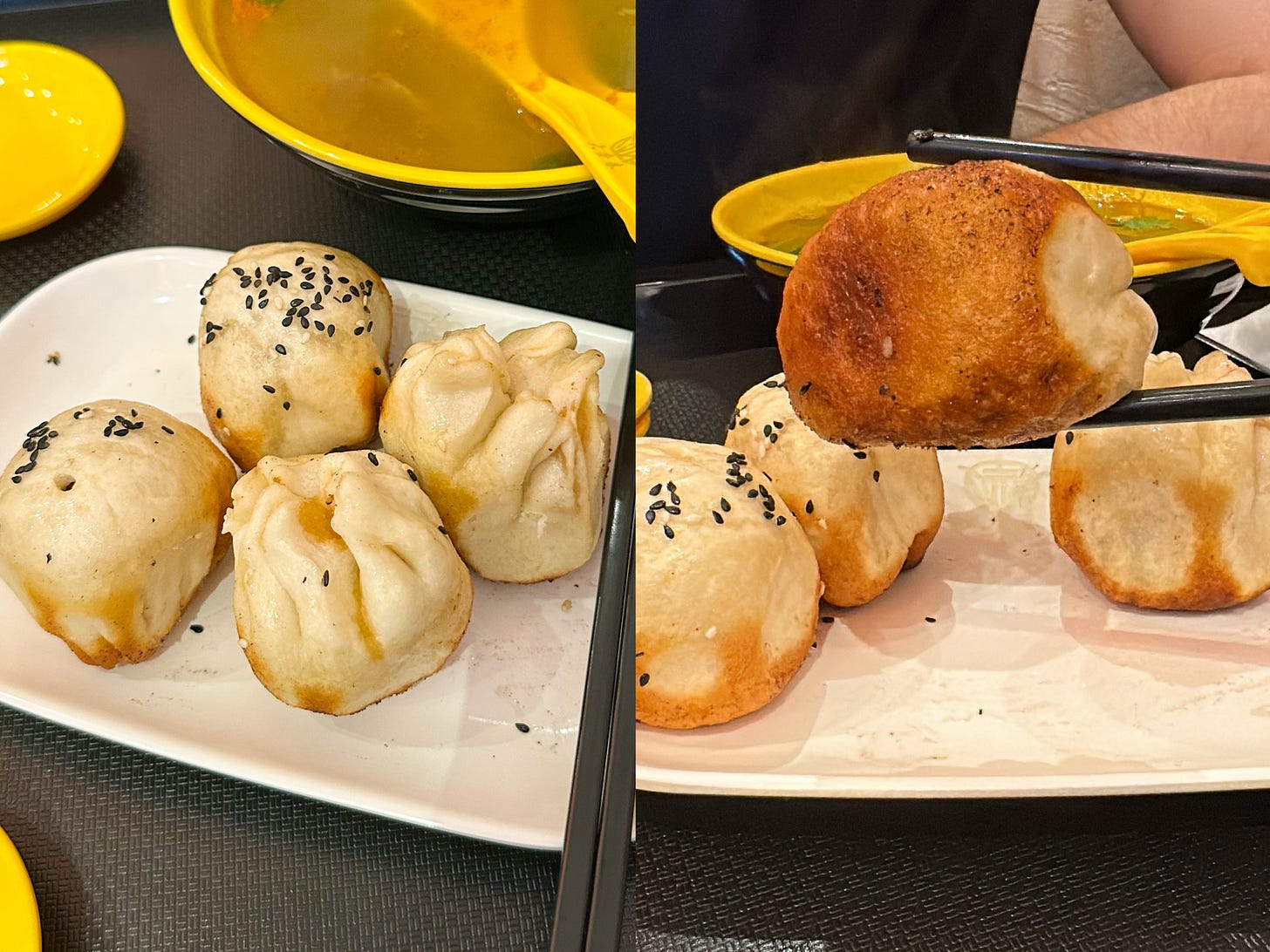

Shengjianbao (生煎包)

Compared to the delicate xiaolongbao, shengjian bao or shengjian mantou (生煎馒头) are pan-fried soup-filled buns that are heartier and more humble.

I first tried them through Xiaoyang Shengjian (a national chain also spread across Shanghai). Still, this time I followed friends’ recommendations to two spots on the same alley—each representing a different style. Shu Cai Ji uses a half-leavened dough (半发酵), which rises after wrapping. Da Hu Chun uses a fully-leavened dough (全发酵), rising both before and after wrapping. The result: a fluffier, thicker skin.

At Shu Cai Ji (舒蔡记), I watched the chef assemble a new batch through an open street-side kitchen. I’d visited another branch in 2023 and was impressed, but this one was even better. The menu is simple, with both shengjianbao and guotie (potsticker dumplings) filled with only pork. A huge flat griddle cooked the batch—first frying, then steaming, sealed tightly under a lid, and the chef has to swirl the pan to ensure even browning. The buns came out with a texture dream: crispy bottoms, fluffy tops, and soft interiors. The filling was more seasoned than xiaolongbao, leaning slightly sweet, but it gave out more juice (thanks to the similar stock jelly added in the filling). Local diners, mostly middle-aged, clearly treated this as a quick lunch spot.

Da Hu Chun (大壶春), a chain where the original shop was crowned a Michelin Bib Gourmand recommendation, offered both pork and pork + shrimp fillings. To distinguish fillings, pork buns were fried, sealed-side up, while shrimp pork ones were sealed-side down. The dough was thicker and chewier—likely due to the longer fermentation—and the filling was leaning on the sweeter side. I didn’t care for the bland curry beef soup, but I did like the plump shrimp and the excellent house chili sauce.

Wontons with Chinese Tapertail Anchovy (刀鱼馄饨)

Shanghai and the surrounding area are famous for different types of wontons, but I came here to try a seasonal specialty: wontons made with Dao Yu (刀鱼), or Chinese tapertail anchovy (Coilia ectenes), a migratory species swimming from the seas into the Yangtze River for reproduction. By the time the fish reaches upstream like Jiangyin and Jingjiang, the salt in its body has dissipated, and the ratio of fat to flesh is just right. This is a sought-after and pricey delicacy, praised as the “most umami of the Yangtze River” which peaks in March and April.. Nowadays, the jiang dao (those migrate to the river) is extremely rare because of overfishing, so most places use hai dao (海刀), fish still living in coastal water. We came a bit late because people believe the best is before the Qingming festival, when the fish bone is still tender.

At Lao Ban Zhai (老半斋), a spacious local restaurant with Yangzhou influences, the setup is divided: there’s a takeout window selling wonton fillings and snacks, and a separate dine-in area for à la carte meals. Two versions of daoyu wontons and noodles were on the menu, and following the cashier’s recommendation, I went for the large wontons. The broth was subtle, and the filling was blended with a bit of pork and only mildly seasoned. It had a mild, lingering fish flavor–more distinct than typical freshwater fish, but nowhere near as pungent as anchovy. What stood out was the texture: softer and more tender than pork wontons, with a light, almost cloudy mouthfeel thanks to whipped egg whites in the mix. Given how bony daoyu is—almost too troublesome to eat whole—turning it into wonton filling is a clever and efficient way to enjoy this prized seasonal fish.

Noodles

Sesame Noodles 麻酱面

While researching sesame paste last year, I came across Shanghai-style sesame-dressed noodles, majiangmian, and added it to my list, though I was skeptical. I grew up with noodles dressed in chili oil and vinegar, and feared a big scoop of sesame paste would feel too heavy.

I visited Wei Xiang Zhai (味香斋)’s original location, and it turned out to be quite hectic. We shared a tiny table at the entrance, with servers and diners squeezing past. A stressful dining experience, but the noodles turned out to exceed my expectations: smooth sesame paste (supposedly peanut butter was also added in it) was quite smooth and balanced, nutty without being cloying, balanced by splashes of chili oil, soy sauce, and rice vinegar.

Scallion Oil & Yellow Croaker Noodles

During my last trip in 2023, I also sampled two other classics. First: scallion oil noodles at Xiaotao Mianguan (小陶面馆). The crispy scallion topping was fragrant, the pork tender and flavorful—it even inspired me to try recreating it at home. Then: huangyu mian, noodle soup with yellow croaker and preserved mustard greens (xuecai) from Dingtele (顶特勒), a 24/7 spot tucked near the busy Huaihai Road. More comforting than exciting, but still worth noting.

Local Benbang Cuisine (本帮菜)

Shanghai’s local cuisine—benbang cai, literally “local gang cuisine”—is often described as “nong you chijiang”浓油赤酱 ( meaning rich oil, red sauce), known for its generous use of soy sauce, sugar, and oil. Renowned Shanghai chef Li Borong described it more precisely: “distinctly seasonal, with fine ingredients, with mastery of heat, and a balance of rustic and refined” (四季分明、选料精细、讲究火功、粗细兼长). For Sichuan-leaning palates, it may taste too sweet or soft, but when done right, it’s a delicate cuisine built on freshness and seasonality.

We ate at Xiao Shihui Jia (小实惠嘉), a small eatery in the residential Jing’an district. As we waited, a yeshu, a typical Shanghainese middle-aged man, stormed out yelling something indecipherable in local dialect. A good sign.

We started with fermented tofu pork belly (腐乳肉), ordered by the piece. A server came over with scissors to cut the slow-braised, bone-in slab into manageable chunks. Food writer Wang Zengqi noted that this Suzhou-influenced dish relies on low heat, Shaoxing wine, and sugar to achieve its melt-in-your-mouth texture. The oil-fried shrimp (油爆虾) showed the cuisine’s quick heat: freshwater small shrimp flash-fried in scorching oil, then glazed in a glossy sweet sauce. Shell and all, they were crisp and addictive. We also had white oil eel (白炒鳝丝), Asian swamp eel stir-fried with cilantro stems and lightly seasoned with white pepper to highlight the eel’s natural flavor. Other minimalist dishes included soy-dressed poached chicken (白切鸡) and stir-fried red amaranth, fresh and simple.

Of course, this is just a small glimpse of Benbang cuisine. In 2023, my close friend Zhaozhao from college took me and a group of friends to a reservation-only spot called 157 Shi Fang (157食坊), where she curated an incredible lineup of local dishes. It was a masterclass in Benbang flavors: red-braised unagi/freshwater eel (红烧河鳗, a textbook example of that glossy, rich oil and soy sauce), eel clay pot rice, drunken shrimp raw marinated in yellow shaoxing wine, and braised stinky tofu with peppers—a milder on the usual deep-fried version.

Ningbo Cuisine & Fusion Kitchens

This time, she took us to a tiny storefront, Bingxian Haiji (炳仙海记), specializing in Ningbo cuisine, from a coastal city about 200 kilometers south of Shanghai. Thanks to the close proximity, the seafood here is delivered fresh from Ningbo each day. Climbing up the restaurant’s narrow stairs, we found a second and third floor—cramped but packed with young diners speaking in different dialects and raising glasses of Asahi draft. The food completely wowed me. As someone who didn’t grow up eating much seafood, this meal felt like a revelation—and officially put Ningbo on my must-eat list.

We started with two wok dishes: stir-fried razor clams and fresh peanut shoots, the latter a first for me. Stir-fried with dried shrimp, the shoots had a tender texture, somewhat between young garlic scapes and bean sprouts, but with a nutty flavor.

Then came a variety of marinated seafood: drunken Ningbo red crab, creamy and rich; a mix of sea snails marinated in soy sauce and wine; and pounded crab. We also had Zao Sanyang (糟三样), a cold trio of edamame, duck tongue, and chicken feet marinated in zao lu—a fragrant brine made as a byproduct of wine production. Next came steamed neritic squid, surrounded by pork wrapped in tofu skin, and finally, a fried rice dish made with a sea creature called haichang (with an unfortunately funny English name), plus golden-fried chicken wings coated in salted duck egg yolk.

Shanghai has also become a culinary frontier, leading the wave of bistros where small eateries serve up creative, fusion-style sharing plates alongside natural wines, all set against a backdrop of sleek, European-inspired interiors. I was lucky to get a seat at Yuanyou tao (园有桃), a Hunan-style fusion bistro dishing out playful, inventive plates like Iberico xiaolongbao and beef tartare with century egg.

Of course, Shanghai’s food scene is far to grasp in one newsletter. And I will patiently wait for my next visit and dream about these buns in between.

List of places and addresses mentioned in the newsletter:

Not every place is listed on Google Maps, you could add the Mandarin name in a Chinese map app Apple Maps, or Chinese Yelp (Dianping).

Jiajia Tangbao (佳家汤包): 90 Huanghe Rd, People's Square, Huangpu District

Lailai Xiaolong (莱莱小笼):506 Tianjin Road, Huangpu District

Shu Cai Ji (舒蔡记生煎菜饭):120 Zhejiang Rd (M), Huangpu District

Da Hu Chun (大壶春), multiple locations: 117 Zhejiang Rd (M), Huangpu District

Lao Ban Zhai (老半斋):600 Fuzhou Rd, Huangpu District

Wei Xiang Zhai (味香斋):14 Yandang Rd, Huangpu District

Xiaotao Mianguan (小陶面馆): 222 Jiashan Road, Xuhui District

Dingtele (顶特勒):494 Huaihai Rd (M), 淮海路中段

Xiaoshihuijia (小实惠嘉): 855 Weihai Rd, Jing'An District

157 ShiFang (157食坊): 1406 Kaixuan Rd, Changning District

Bingxian Haiji (炳仙海记):354 Wulumuqi Road (M), Xuhui District

Yuanyoutao (园有桃):167 Xinle Road, Xuhui District

You are an excellent writer! Your descriptions of everything are so vivid that it feels like we are right along there eating with you. Reading this made me miss China so much I got teary eyed. Thank you!

Oh wow! Thanks for sharing this delicious itinerary - I'm so jealous and saving this for if I ever get to go back to Shanghai!