Welcome to Chill Crisp, my internet corner of thoughts about food and recipes with context. Mostly Chinese food I’ve been eating my whole life and new flavors inspired by travel, research and a splash of creativity.

This is part 3 of cooking Sichuan classics from an old cookbook. You can read about Mapo Tofu in my last newsletter.

Kung Pao chicken, or Gong Bao Ji Ding (宫保鸡丁), requires no elaborate introduction. You know its status is revered when it sounds like its original Chinese name. Stir-fried chicken pieces was was always my go-to for cooking a quick nutritious meal as a beginner cook/student, with the dollops of Lao Gan Ma and leftover veggie in my fridge. At one point, I got more ambitious than Lao Gan Ma.

Then I learned about Kung Pao Chicken. What fascinates me about this dish is the layering of flavors: it’s a well rounded combo of all different flavours, without one being too prominent. Also one with very long origin story. Born with influence from regional cuisines, now one of the most famous Chinese dishes (even Trump was served it), it marks a perfect tale about immigrating. Scroll down to the bottom to see my recipe and watch the video on Instagram!

The Tale of Origin

Among the many narratives surrounding its creation, the most prevalent traces back to Ding Bao Zhen, a Qing dynasty official in Sichuan Province and bearing the title of Gong Bao (宫保). It is widely believed that this dish's preparation draws inspiration from various regional cooking styles that followed Ding Bao Zhen's life, including the fiery chilis of his hometown Guizhou and the adept chicken stir-fry techniques of Shandong. Fuschia Dunlop wrote about this fascinating story here.

The book <History of Sichuan Cuisine> reveal that the earliest semblance of this dish can be traced back to stir-fried chicken pieces enjoyed during the Yuan Dynasty in southern and eastern China. The author Lan Yong speculates that its precursor could be the vinegar-infused stir-fried chicken (醋溜鸡) that was popular in Chongqing area in 1920s.

Crafting the Sichuan Version of Gong Bao

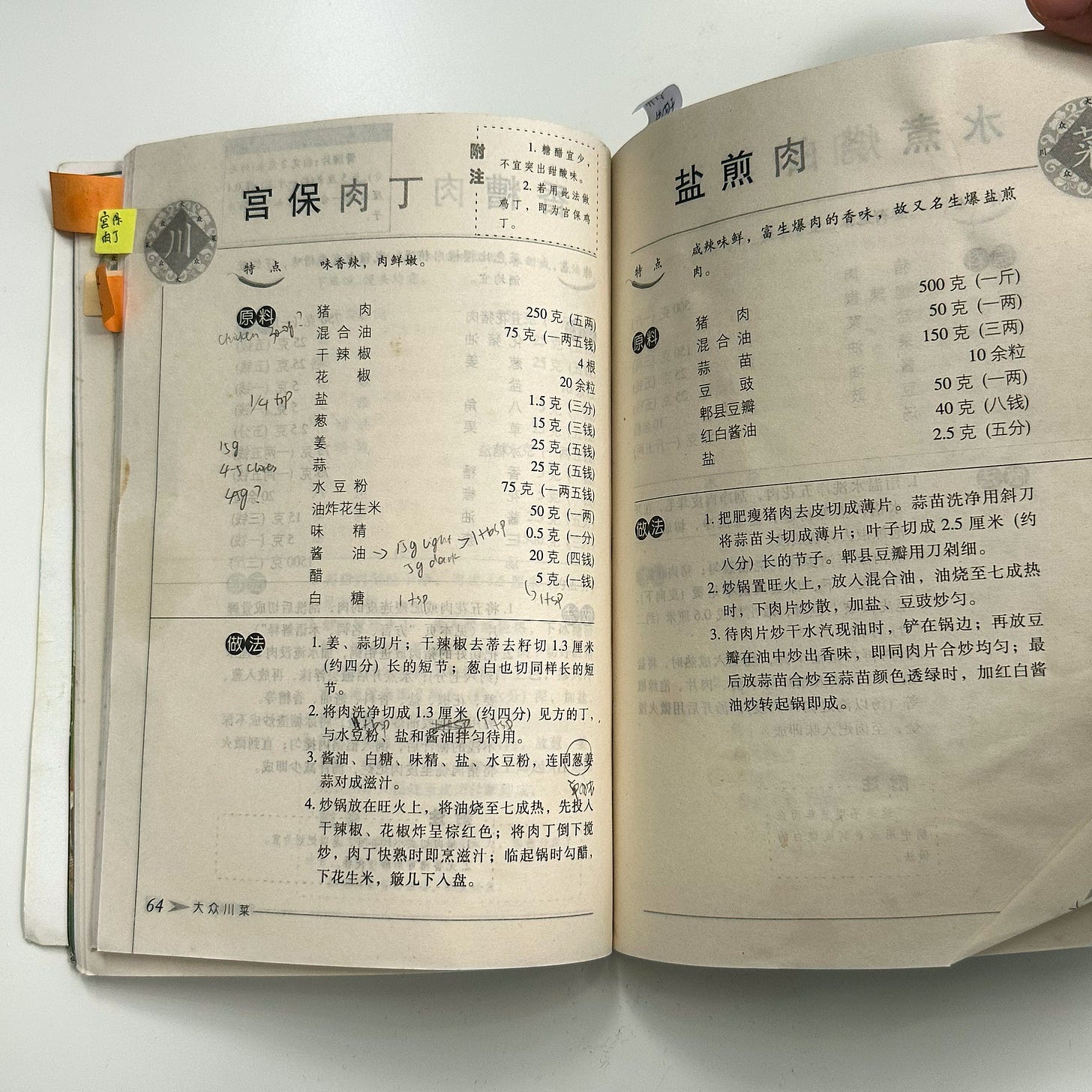

The recipe I'm based on is a pork version, which is also quite popular in Sichuan. You can find a series of Gong Bao dishes in Sichuan restaurants.

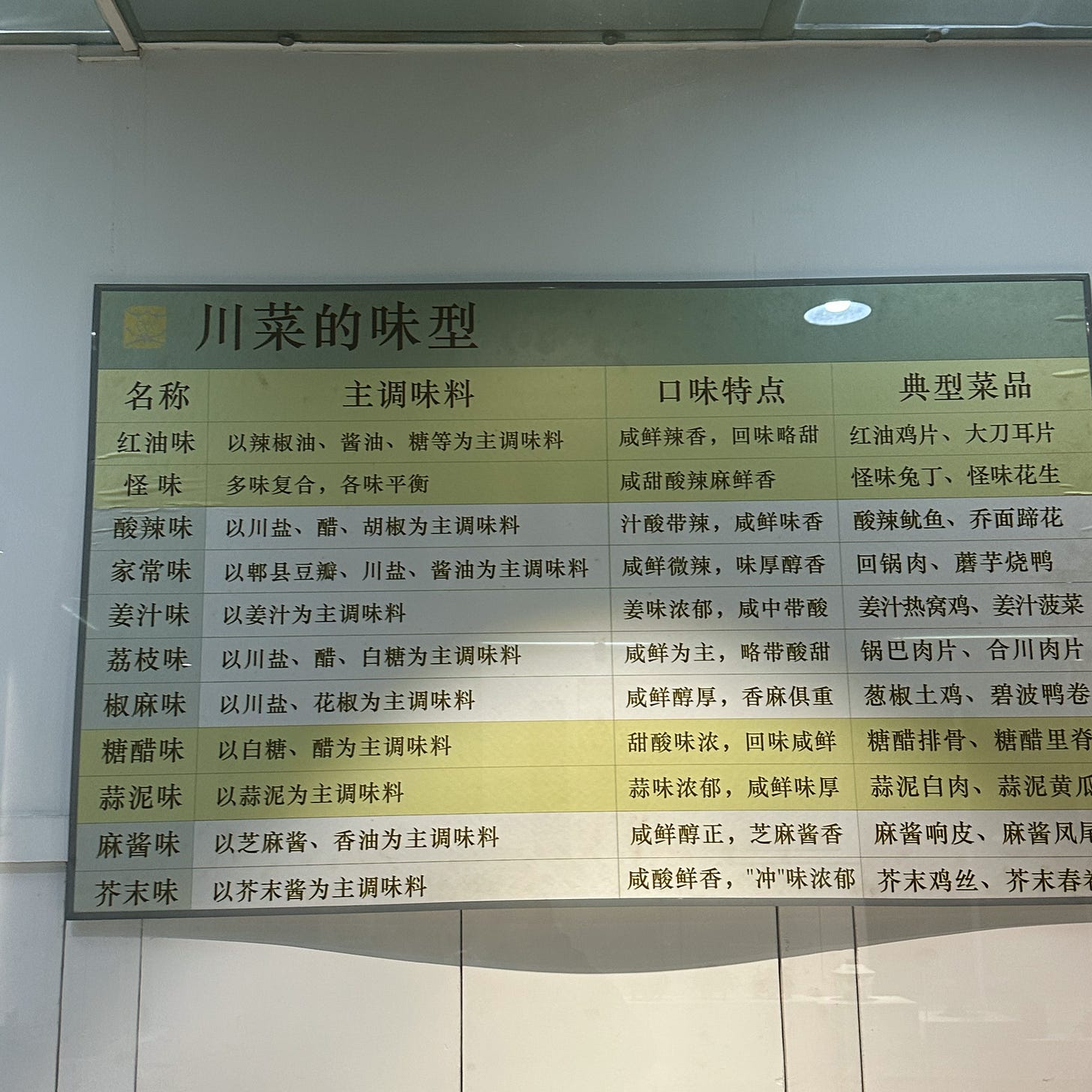

In Sichuan cuisine, Kung Pao chicken is categorized as a combined flavor profiles of scorched chili flavor (hu la wei, 糊辣味) plus lychee flavor (li zhi wei, 荔枝味) among the 23 complex flavors (Ma la is also one of them). This means a combination of savory, umami, with a mellower sweet and sour, and a hint of spicy and almost too-hard-to-notice numbing. The Lychee flavor might be hard to grasp if you never had this delicate fruit before but is to distinguish from the more pronounced sweet and sour (tang cu, 糖醋味) in dishes like sweet and sour ribs. This was also instructed by the book above: be mindful of sugar and vinegar.

Start with scorching a fair amount of dried chili and pepper. I used Er Jing Tiao chilis (like this one), but other dried red chilis (I’d avoid Indian dried chilis as they’re so fiery) work. Go gentle with a medium heat and carefully observe as the chilis darken but not burnt. Since they’re there to infuse the oil, you could also fetch them out before adding the chicken and then add them back for styling. The Sichuan-style Kung Pao Chicken needs to be done in one go (this is called 一锅出 hi guo chu), while other versions might involve frying each ingredient and tossing them together.

The lychee flavor comes from the sauce by adding a small amount of sugar and Chinkiang vinegar. Vinegar is added at the end of the cooking so it doesn’t lose too much flavor, as well as the peanuts for its crunchiness. The final dish should swim in a thick and dark brown-reddish sauce. I used a combination of dark and light soy sauce, both in the chicken marinade and the sauce. If your dish doesn’t look at restaurant, it probably lies on the dark soy sauce. This pan sauce can work very well for other proteins like pork, shrimp, and even vegetarian options like cauliflowers and oyster mushrooms.

Though all the Kung Pao chicken I’ve had always have some vegetable components, such as celtuce or carrot, I do find the minimal version with leek and peanuts nice, to focus on the chicken and sauce. The director of the Museum of Sichuan Cuisine suggests using a small spoon to have everything on it: a piece of chicken, dried chili, leek, peanuts a kernel of Sichuan pepper, and chew.

I'm more into the notion that Kung Pao Chicken is an evolving dish, starting from the very beginning. The authenticity is no longer the only standard and you shall enjoy your own version, but maybe look for the lychee next time!

Recipe

300 g boneless skinless chicken thigh

3 tbsp oil

4 dried chili

20 whole Sichuan peppercorns

1/2 tsp salt

1/2 leek

15 g ginger

4 cloves garlic

starch water (2 tsp starch + 3 tbsp water)

50 g fried peanuts

1.5 tbsp light soy sauce

2 tsp dark soy sauce

1 tsp dark rice vinegar

1 tsp sugar

a pinch of MSG (optional)

Thinly slice ginger and garlic. Remove the stems and seeds of dried chilis and cut into small pieces (approx.2 cm). Cut leek into rings of 1 cm thickness.

Cut chicken thigh into bite-sized pieces, mix with 1 tbsp of the starch water, 1/4 tsp salt and 1 tsp of the light soy sauce. Mix with your hands until the moisture is absorbed.

To make the sauce: mix remaining light soy sauce, remaining starch water, dark soy sauce, sugar, 1/4 tsp salt and MSG if using. Mix until well combined.

In a frying pan, heat the oil over medium heat. Add dried chilli and Sichuan pepper, fry until the color of chili turned dark red。

Then add the chicken immediately, let one side fry first before stirring, then stir fry. Add ginger, garlic and leek mix, fry until the chicken is cooked. Then add the sauce in a few batches, mix until the sauce thickens. At the end of cooking, add vinegar and fried peanuts. Serve immediately.