Beyond the "Food Desert": Eating Through Hangzhou

Morning market, wok noodles, stinky tofu, plus the best tea museum

Just an hour and a half from Shanghai by high-speed train, Hangzhou was the second stop on our trip, chosen mostly for sightseeing. As the capital of Zhejiang province and a cultural jewel of the Jiangnan region, Hangzhou has long been romanticized by poets for the beauty of West Lake, its imperial legacy, and its rich culinary tradition. It’s also the birthplace of Longjing (Dragon Well) tea, one of China’s most revered green teas, and home to legends like the tale of the White Snake, which became a hit TV drama and a pop culture sensation in the 1990s.

Jiangnan cooking is known for its subtle, delicate, and seasonal flavors, and Hangzhou’s version is even lighter and less sweet than nearby Shanghai or Suzhou. However, fast forward to today, despite its rich heritage, the city has developed a somewhat unfair online reputation as one of China’s so-called “food deserts” (美食荒漠).

I wasn’t in a position to argue. My only memory of Hangzhou food dates back to a high school trip 15 years ago, and meals at Grandma’s Home (外婆家), a restaurant chain known for its 3-yuan mapo tofu, which later expanded to Chengdu (and even New York). So I came with low expectations. But I left with something better: proof that Hangzhou’s food scene is very much alive—if a little hidden.

At the Market: A Glimpse Into Hangzhou’s Kitchen

I began exploring at a local market—always the best way to get a feel for how a city eats and lives, even if we weren’t cooking on this trip.

Hangzhou’s Da Ma Nong market sits in a narrow open-air alley downtown. It’s not the biggest in town, but it’s lively with locals weaving through on mopeds. Stalls overflow with ingredients that builds Hangzhou’s cuisine: salt-brined mustard greens (xuecai), dried fish, fresh eel, frogs, and seasonal produce like amaranth, bamboo shoots, loquats, and cherries. You’ll also find semi-prepared dishes like tofu sheet rolls (千张包) or deep-fried gluten balls stuffed with pork (面筋塞肉), ready to be steamed, braised, or served in soup.

The market was also a window into local breakfast and street food. I tried cong bao hui (葱包桧), a thin wrap of scallions and fried dough (youtiao) pressed in a spring roll sheet and brushed with chili and sweet sauce. Hui, the local word for fried dough sticks, is named after the infamous Qin Hui, who’s been symbolically “fried” in public memory for centuries. Next were egg dumplings, made by ladling beaten egg onto a hot plate, then folding in minced pork before the egg sets. Typically served during the New Year for their resemblance to gold ingots. On their own, they were tender and savory. I imagined them better floating in a bubbling clay pot, the way I first encountered them at a Nanjing-style spot in Berlin.

Across the alley, we found a few eateries with seats. One sold tiny wontons (小馄饨) in hot broth with seaweed, egg threads, and a nice punch of white pepper. Their shumai came stuffed with pork and bamboo or jicai (shepherd’s purse), a spring vegetable beloved across Jiangnan. Next door, a shop offered one-yuan pot-sticker buns and dumplings smaller and fluffier than the Shanghai variety, but just as satisfying.

Wok Noodles, Made to Order

Hangzhou has thousands of noodle eateries scattered throughout the city, which is believed to be a legacy of the northerners who migrated to the south through different historical periods. Uniquely, the noodles here aren’t called mian (面), but chuan (川)—a word that once meant blanching (汆, cuan) and now refers to the city’s signature styles.

The most iconic is pian’er chuan (片儿川), a noodle soup with xuecai, pork slivers, and bamboo shoots. Ban chuan (拌川) refers to stir-fried noodles with various toppings—often soy-glazed pork liver, kidney, or braised meats. What sets Hangzhou apart is that each bowl is made to order, stir-fried fresh in a wok, rather than pre-assembled like in many other regional noodle styles.

I visited Xiaogou Mianguan (小狗面馆, literally, “Puppy Noodles”), tucked into a residential street. The shop has an open kitchen with multiple burners, where chefs cook every bowl of noodles individually. For soup noodles, pork, bamboo, and mustard are stir-fried before water is added to form a milky broth. The noodles are boiled separately, then added to the soup. Stir-fried versions are cooked hot and even faster, liver and kidney tossed just for seconds to stay tender, then combined with noodles, stir-fried over high heat to give them the amazing char and wok hei (see the video below of making ban chuan).

I didn’t expect to love these noodles. The soup was warming and subtle, with deep umami from the mustard greens and crunch from the bamboo. The stir-fried bowl had more character: charred edges, tender toppings, and a smoky richness. The owner suggested we try jiang ya (酱鸭), a local specialty: ducks salted, marinated in a soy-spice brine, sun-dried for days, and then braised when serving. The result was a firm and springy texture and a deep, savory glaze. Even with the filling noodles, I savored every bite.

A Taste of the Classics

To try more iconic Hangzhou dishes, I ended up, perhaps predictably, at the chain store Grandma’s Home (not the best choice in hindsight). I ordered the Longjing shrimp, West Lake beef soup, and of course, their famous (now 10-yuan) mapo tofu.

Longjing Green Tea Shrimp (龙井虾仁) is one of the most famous Hangzhou dishes: freshwater shrimp lightly coated in egg white and starch, velveted in oil, and stir-fried with brewed Dragon Well tea. The version I tried featured small, bouncy shrimp, but the sauce was a bit too thick, and the tea flavor was barely noticeable. Given how expensive Longjing tea is by the kilo, I suspect corners were cut. Legend says it was created accidentally during a Qing emperor’s visit, and it famously appeared on the menu of the state dinner. Though I doubt this rendition held up to that level.

What I did enjoy was the West Lake beef soup (西湖牛肉羹), a lightly thickened broth with beef, tomatoes, and delicate egg drops. Normally, I prefer clear soups (tang), but this one struck a nice balance—velvety but not gloopy, savory with just the right tang. It reminded me of a cross between egg drop and hot-and-sour soup (some believe this dish is a variation of hu la tang, 胡辣汤 from Henan province). In Invitation to a Banquet, Fuchsia Dunlop writes about the history of this type of thick stew-like soup, geng (羹), including another Hangzhou classic, Mrs. Song’s fish soup. I had assumed I didn’t grow up with anything like it, as it felt more northern to me. But then, to my surprise, I encountered similar versions back home in Sichuan, a starchy sour soup either with beef and croutons or with egg drop and cilantro.

Later, we met a friend from Zhejiang who now lives back home after years in Berlin. She took us to Jiangnan Yi (江南驿), a restaurant where the owner blends traditional Jiangnan cuisine with influences from her travels. The menu, handwritten on recycled paper, offered dishes like jiao ma ji (椒麻鸡), or numbing chicken—a Xinjiang interpretation of Sichuan’s classic poached whole chicken in broth.. A steamed sunke fish (marble goby, 笋壳鱼) followed, subtly perfumed with green Sichuan peppercorns, floral but not numbing, which allowed the delicate and fresh flesh to shine.

We also tried pork riblets braised in fermented tofu, a deeper, funkier variation of the version I’d had in Shanghai. And then came the surprise standout: fried stinky tofu dusted with toasted seaweed shreds (tai tiao 苔条, extremely thin threads of seaweed) and pine nuts. Zhejiang-style stinky tofu is soaked in the strong fermented vegetable brine. Unlike the aggressive-smelling street food version, this one had a gentle aroma, a pleasant crunch, and a rich, nutty flavor. It was, hands down, the best stinky tofu I’ve ever had. The meal ended with a seasonal vegetable stir-fry of bamboo shoots, sweet peas, and local ham. You could sense the restaurant’s focus: seasonal ingredients, traditional roots, and playful experimentation. I’d go back in a heartbeat, and with more friends to share the menu.

Tracing Tea from Museum to Temple

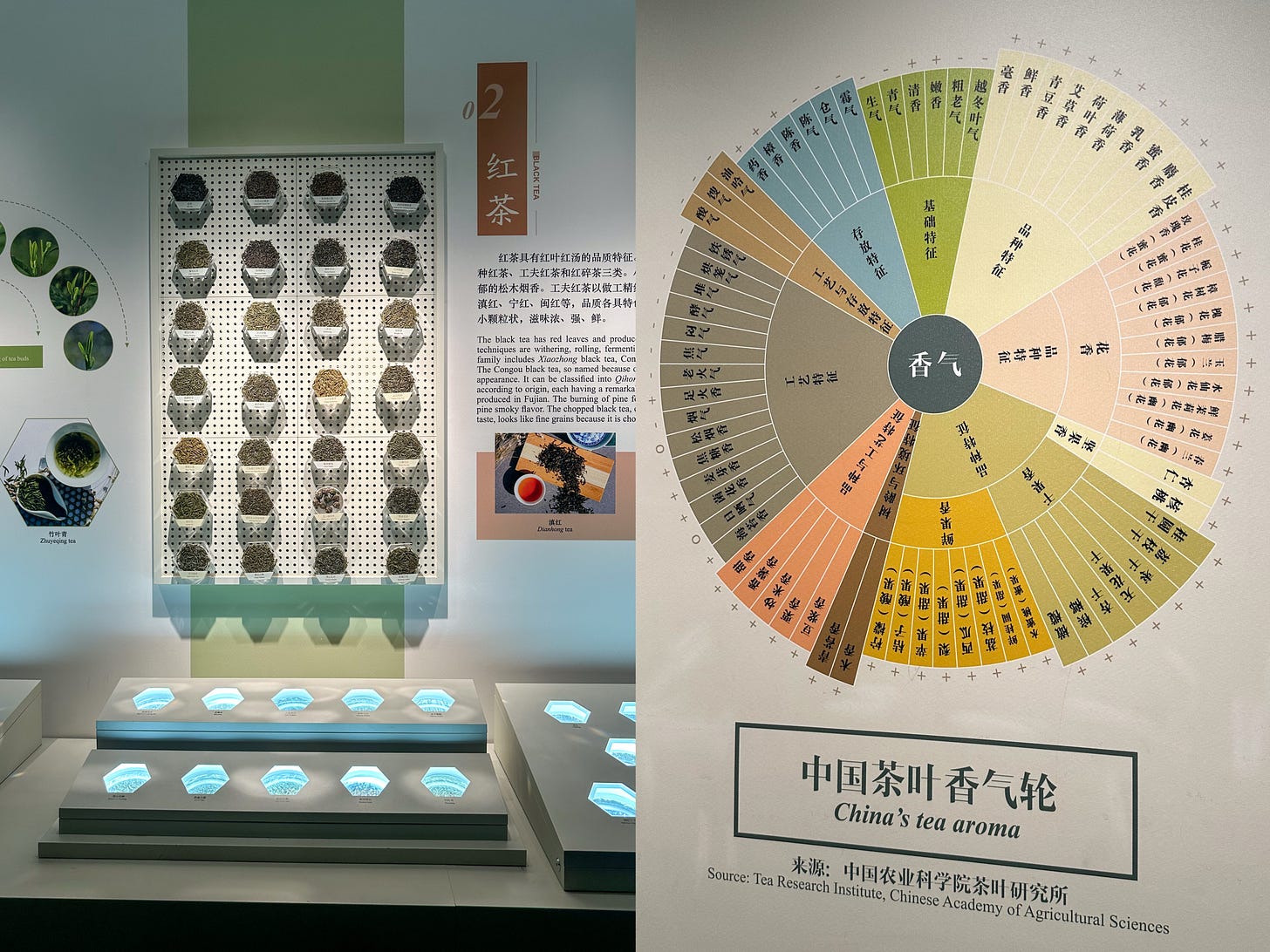

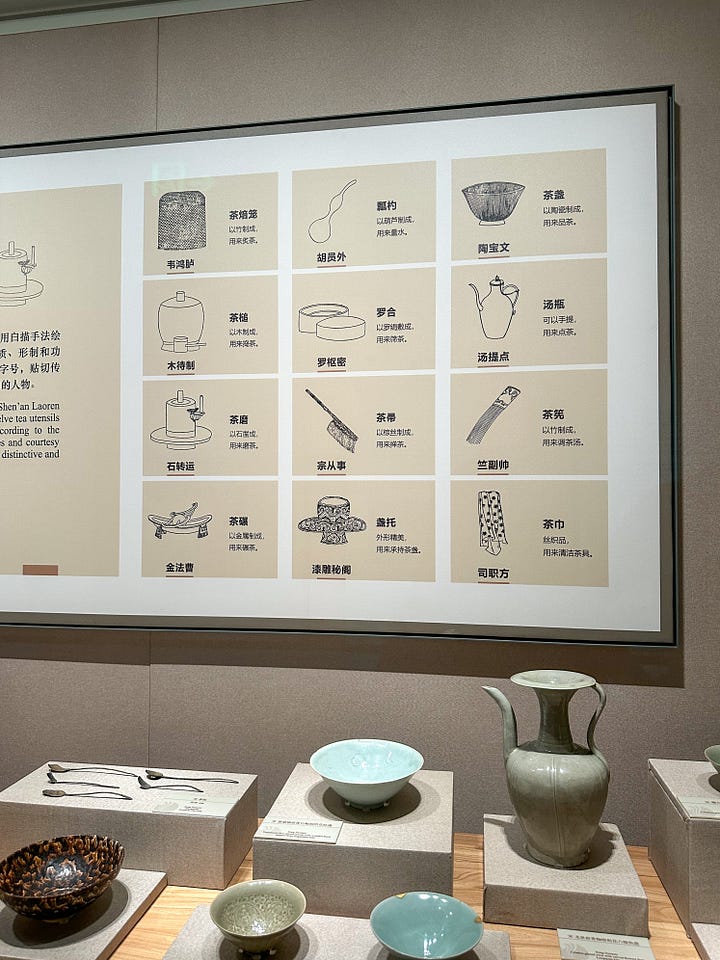

The China National Tea Museum has two locations, and we visited the one tucked into the tea fields (Shuangfeng Guan). It turned out to be one of the best-curated food museums I’ve been to: informative, interactive, thoughtfully designed, and refreshingly free of commercial overkill. The exhibits are divided into several sections covering the history, cultivation, processing methods, and cultural traditions of Chinese tea. You can learn how different varieties—green, black, yellow, white, oolong—are made, and explore the samples of nearly a hundred regional teas from across China.

One gallery featured color, taste, and scent wheels of Chinese tea and an interactive aroma quiz station. We were quizzed on different smells pumped through vents—herbs, spices, oils. I was pleased to recognize the nutty note of sesame oil without hesitation. Other sections explored the origins of tea drinking, how practices evolved over dynasties, and the terroir of Longjing itself, including how the famous green tea is processed. For someone who loves museums and drinks tea regularly—but wouldn’t claim to be an expert—it was the perfect place to soak up knowledge. And it’s free, although we did pick up a bag of spring-harvested Longjing from a nearby farm.

Later, we found a tucked-away teahouse inside Yongfu Temple, perched just uphill from the tourist-packed Lingyin Temple. The temple grounds were tranquil, surrounded by blooming hydrangeas in blue and pink.

The monks there cultivate their own Longjing green tea and serve it in a serene, minimalist teahouse overlooking the hills. We sipped two glasses of Mingqian Longjing (harvested before Qingming festival in April), accompanied by an assortment of snacks: roasted sunflower seeds, salted peanuts, and the hush of stillness. For a city as bustling as Hangzhou, the silence felt almost unnatural—yet perfectly fitting, given Longjing’s historical ties to a Buddhist monk called Biancai, who helped bring the tea to renown in Song Dynasty.

I left with a reassuring realization: Hangzhou is anything but a food desert. That said, the frustration is understandable. Like many rapidly growing megacities, Hangzhou has seen chain restaurants edge out smaller mom-and-pop spots. Social media hype often overrides local word-of-mouth.

At the same time, for younger eaters drawn to spicier and heavier flavors, Hangzhou’s light, seasonal style may seem underwhelming. Banquet-style dishes like West Lake Vinegar Fish or Longjing Shrimp require top-quality ingredients and technique, and aren’t easy to find unless you know where to look—or are willing to spend. But for those willing to look, Hangzhou’s food culture still runs deep.

Thank you for another interesting and enjoyable read, a beautifully crafted piece.

Ive been to that museum, some years back - such an extensive assortment of teas displayed and explained. That duck looks delicious!! My enduring memories of Hangzhou cuisine is the famous Beggar's Chicken. 叫花鸡.