Happy weekend! This week is another one of Chinese Pantry Talk (find the archive here!) We’re not talking about but also making one of my favorite sweet Chinese ingredients, lao zao (sweet fermented rice).

Last winter, I stumbled upon a small shop specializing in sweet fermented rice (lao zao) near Yulin Market in Chengdu. At Wang’s Secret Lao Zao, big yellow enamel bowls of homemade fermented rice are sold by weight, with flavorings like rose, osmanthus, and goji. Their offerings also include tangyuan dough, bing fen jelly, and douhua desserts, depending on the season. I got a lukewarm douhua with osmanthus lao zao, savoring the smooth tofu submerged in the floral, subtly sweet soup.

I've loved lao zao since I was a child. Although I couldn't bring the beautiful homemade versions back to Berlin, they inspired me to try making it myself. So, I ordered the starter and patiently waited for warmer days to arrive.

What is sweet fermented rice?

This condiment, also known as fermented rice wine, usually comes in a jar containing both sweet, mildly alcoholic liquid and soft rice grains. It's called lao zao (醪糟) in Sichuan but is also known as jiu niang (酒酿) and tian mi jiu (甜米酒) in other parts of China. Traditionally, it’s made by fermenting cooked sticky rice or rice with a wine yeast(jiu qu) in a warm environment for a few days. As a by-product of rice wine making, fermented rice has a history dating back thousands of years. It was first recorded in the Rites of Zhou (circa 3rd century BC) as a sweet, light alcoholic drink known as 醴 (li).

Each region has its own starter and production traditions, resulting in variations in taste—some more sweet, others more sour. While mass-produced sweet fermented rice is widely available in supermarkets, some families still make it from scratch or buy it from small producers at local markets.

How to use sweet fermented rice?

Sweet fermented rice is ready to consume. You can also enjoy it in drinks with chilled milk or consume it directly. It’s mostly used in sweet dishes, both chilled and warm, such as tang yuan (sticky rice balls), bing fen (cold jelly dessert), and sweet douhua. It also finds its way into savory dishes as a marinade, in braised fish and meat, and even in pickles, doubanjiang, and hot pot soup bases to add sweetness and umami. . I recently learned that homemade fermented rice can replace yeast to make a dough starter (lao mian, as shown in this video), and I tried it with a small batch of baozi and mantou, which worked nicely (not as fluffy but with a natural sweet taste).

According to traditional Chinese medicine, sweet fermented rice is consumed to dispel coldness and nourish the body during menstruation or postpartum recovery (known as sitting the month). My mom recalled that when she gave birth to me, new moms were advised by the older generation to eat poached eggs in warm fermented rice with dark brown sugar.

Besides the poached egg, one of the easiest ways to enjoy fermented rice is to make a popular dessert called Jiuniang Yuanzi 酒酿圆子 (in Sichuan it’s called 醪糟粉子). Cook store-bought or homemade mini sticky rice balls. Cook store-bought or homemade mini sticky rice balls (recipe) and add a few spoonfuls of sweet fermented rice to the hot broth, along with goji berries and sugar syrup.

You can easily find ready-made lao zao in most big Asian grocery stores, and it stays fresh in the fridge for a few months. While there may not be a wide selection of brands, look for those with cleaner ingredients (preferably without added sugar) and a fresh production date. I usually go for mi popo (米婆婆), made in Xiaogan in Hubei province, a renowned production region (this documentary piece shows how rice wine is produced here).

Homemade sweet fermented rice

Making sweet fermented rice at home is a simple fermentation project, perfect for warmer days in summer. And it’s surprisingly easy. For someone how has limited fermentation experience (mainly in making kimchi), I tried it twice, and both came out successful.

The recipe

Ingredients

250g dried sticky rice

0.6g store-bought jiu qu (Chinese wine yeast)

150ml cooled boiled water or bottled water

(Every jiu qu works differently, so refer to the package instructions of your fermentation starter. Mine recommends 1.2g starter for 500g rice. A scale would be very helpful here!)

Soak the sticky rice in water for at least 6 hours or overnight until it’s soft enough to be easily broken with fingers. Rinse and drain the rice (no need to dry it).

Wet your bamboo steamer and cloth, then add the drained rice in a thin layer. Poke a few holes in the rice. Set it over boiling water and steam over medium-high heat until the rice is cooked but still plump and not mushy, about 40-50 minutes.

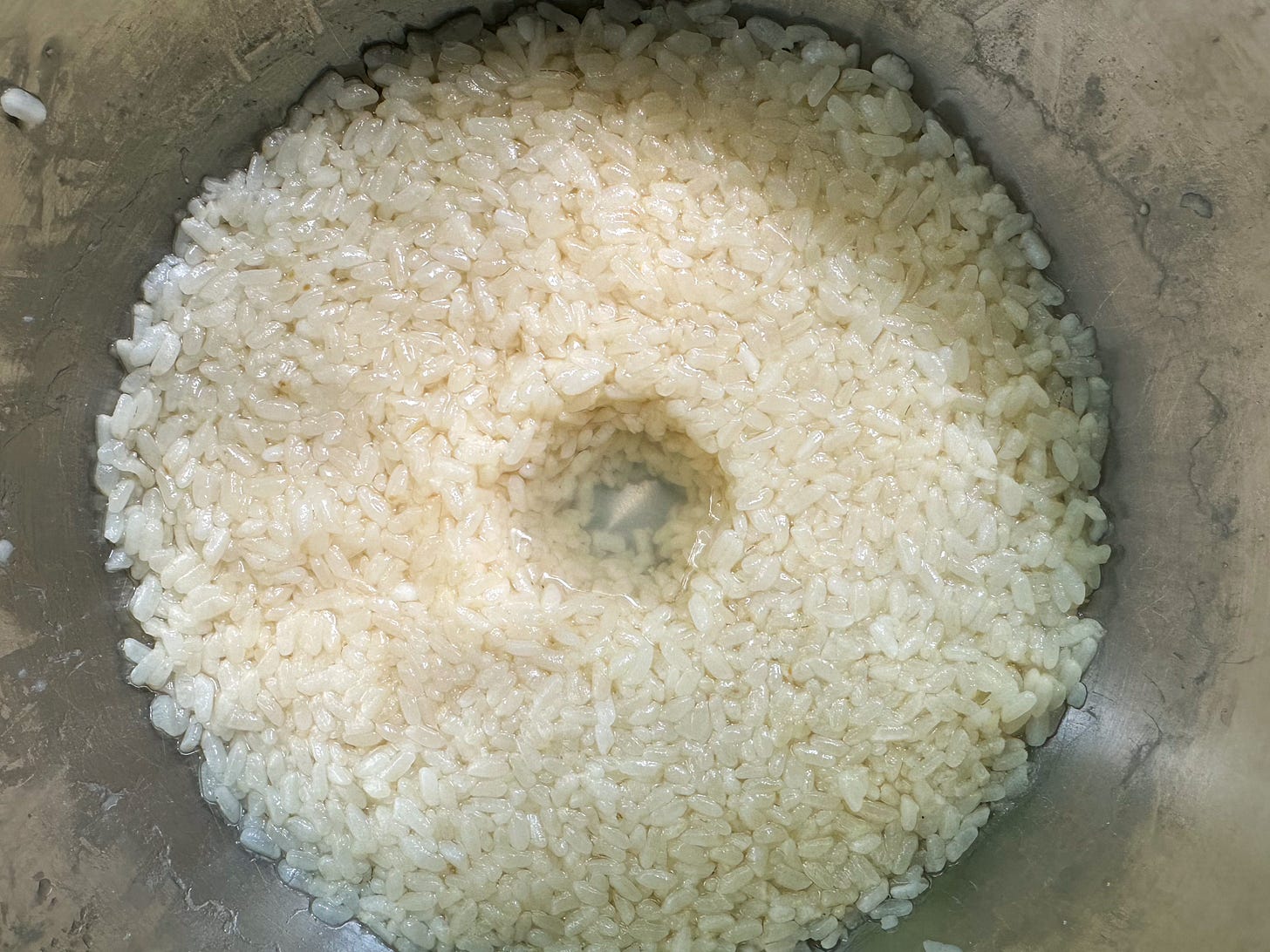

Transfer the rice to a sterilized bowl or container and let it cool until lukewarm (about 28ºC). If using yeast balls, place them on a piece of parchment paper, fold and roll to crush them into a fine powder. Add the yeast and water in batches, mixing to ensure each grain is moist but without excess water. Press down with a spoon and create a small well in the middle.

Cover with plastic wrap or a loose lid and leave in a warm place to ferment for 24 to 72 hours, depending on the temperature. When the fermented rice is ready, the well should be filled with a sweet, slightly alcoholic liquid. Taste with a clean spoon.

When the rice is fermented to your liking, dilute it with 200-250 ml of cooled boiled water or bottle water, transfer to an air-tight jars then store it in the fridge. Use within one week (some say it stays longer, judge by the taste of your ferments).

Tips for homemade fermented rice

I received detailed instructions from my yeast seller, and I referenced some resources in Chinese, the blog articles from the wok of life, and China Sichuan food.

Temperature: Temperature control is key. The instructions recommend fermenting the rice at around 25-28°C (77-82°F), though some suggest up to 35°C. On days when the temperature was 25-30°C (likely cooler indoors) in Berlin, it took about 36 hours to see the well start to fill with liquid. After 48 hours, the rice was soaked in liquid and puffed up. At this point, store it in an air-tight container, then transfer it to the fridge to slow fermentation. It could take 2-4 days depending on the temperature, but do check daily. If left longer, it will become more alcoholic and less sweet. During colder days, you may need to use a yogurt machine, or oven, or wrap it in a thick blanket, as traditionally done in China.

Rice: I use short-grain, round sticky rice from Taiwan, which is believed to result in sweeter liquid. Or you can use long-grain sticky rice produced in Xiaogan Hubei if you can find it. You can use a rice cooker but be mindful of the water, as the rice should not be mushy.

The fermentation starter (wine yeast): Jiu qu (酒曲) is translated as Chinese wine yeast, used to make alcoholic beverages in Chinese cuisine, similar to Japanese koji. For this sweet fermented rice, you normally can find specialised starter, sometimes also called tian jiu qu. These come in both ball and powdered forms. If you can't find them in your local Asian grocery stores, they are available online under names like wine yeast, rice leaven or distiller’s yeast. Here’re some links: Anqi powdered jiuqu (US, Germany); Shanghai wine yeast balls (US, UK)

Sterilization: It's essential to sterilize all utensils to prevent mold and cross-contamination, just like when making jams or other ferments. Also when you taste the liquid, use clean spoons.

Is the water in the ingredients used for soaking? Or can you use tap water?

I ate at shoo long kan / xiao long kan hotpot and their mala soup base contains Lao zao/jiu niang. I’m currently 7w pregnant, would it be okay? I only dipped some meats in the soup and didn’t drink it. Thank you🙏🏼