If you’re new here (hi and welcome!), this series is where I dive deep into one Chinese ingredient—or a group of them—exploring their history, how they’re made, and how to cook with them. You can already find guides on doubanjiang, Chinese black vinegar, Sichuan pepper, soy sauce, fresh tofu blocks, tofu products, sesame oil, and sesame paste.

I’ve been cooking with different Chinese preserved vegetables at home in the past year—partly for recipe testing, partly to satisfy cravings. I didn’t realize how confusing all the names with “cai” could be until my partner asked me one day: What’s the difference between all the Cais? In English-written recipes, they often get lumped together as “Chinese pickles” or “preserved vegetables.” But if you’re hunting for Yacai to make Dan Dan noodles and end up with something else, it can be frustrating.

So here’s a breakdown of a few common preserved vegetables you’ll see in Chinese—especially Sichuan—cooking: Yacai, Zhacai, Caipu, and Xuecai. These pantry staples are cheap, come in small packs, and have a long shelf life. I always keep a box stocked and refill them whenever I hit the Asian grocery store.

What Are Chinese Preserved Vegetables?

Chinese preserved vegetables, sometimes called Chinese pickles (in Mandarin: 腌菜, 咸菜), are broad terms that cover a huge variety of regional specialties. These vegetables are preserved with salt and/or seasonings like spices, soy sauce, sugar, or vinegar. Some undergo fermentation. Common ingredients include leafy and stem mustards, radish, Chinese turnip, and napa cabbage. These generally fall into three categories: sauce-preserved (eg, soy paste cucumbers), salt-preserved (eg, zhacai, xuecai), and lacto-fermented (eg, paocai or suancai).

These preserved veggies are incredibly versatile—they can be served as sides or folded into dishes to add a punch of flavor and texture. Think of them as the Chinese pantry’s answer to olives or kimchi: savory, funky, and full of character.

Their signature flavor is savory and umami-rich, known in Chinese cooking as 咸鲜 (xian xian). Beyond flavor, they bring a satisfying crunch or chew, depending on the variety. If you’re new to them, start simple—sprinkle them over noodle bowls or mix them into fried rice. Just keep an eye on your salt.

Yacai 芽菜

If you’re into Sichuan food, you’ve probably come across Yácài in dishes like Dan Dan noodles or dry-fried green beans. Often translated as “preserved mustard greens,” Yacai is dark brown, tender-crisp, umami-rich, savory, and super fragrant.

Yacai originated in Yibin, a city in southern Sichuan, during the Qing Dynasty. That’s why it’s also known as Yibin Yacai (formerly Xufu Yacai) with geographical indication1. It’s made from a local leafy mustard variety called erpingzhuang (二平桩). The stems are cut into strips, dried, salted, mixed with brown sugar syrup and spices, and fermented in barrels for months—sometimes over a year2.

Yacai is a staple for building umami in Sichuan dishes like Dan Dan noodles, Yibin burning noodles, steamed pork belly (烧白), pastries (such as Ye’erba 叶儿粑), bao buns, and stir-fries. The most common version in stores is Suimi Yacai (碎米芽菜), pre-chopped and ready to use. Because it’s chopped small, it clings well to the ingredients. One quick stir-fry with Yacai and chicken I developed last year has become a go-to 20-minute lunch.

How to Cook with Yacai:

Yacai is mostly used in cooking. It can be salty straight out of the package—I like to give it a rinse or soak it for 5 min., then drain it well. For cooking, try frying it with a little oil or dry-toasting it to bring out more aroma.

Yibin Burning Noodles (recipe coming soon!)

Zhacai 榨菜

Zhàcài, often translated as “pickled mustard stem,” is made from a type of stem mustard called qingcaitou (青菜头)3. The stems are wind-dried, salted, pressed to remove moisture, then seasoned and left to ferment for months. The name Zhacai means “pressed vegetable,” a nod to the traditional method of using wooden presses. The result is crunchy, light-beige or reddish-brown slices or slivers—firmer than Yacai—with a savory-sweet flavor that’s sometimes mildly spicy.

The best-known types come from Fuling, Chongqing, and Zhejiang. Fuling’s version is the most famous and widely available—even outside China. You’ll find both whole bulbs and ready-to-eat snack packs at Asian grocery stores. I prefer the small packs—they’re so versatile that my parents even travel with them (if we want to cook at the destination)! Heritage Chongqing brands include Wujiang (乌江) from Fuling and Yuquan (鱼泉) from Wanzhou. They come in different flavors and cuts—thin slices, slivers, etc. For cooking, go for the less-seasoned types like fresh crispy (清爽) or light crispy (清香). The spicy Mala flavors (麻辣) are great as sides for rice.

How to Use Zhacai:

Eat straight from the pack with rice, congee or noodles. Chop it small and use as a topping for steamed eggs, tofu pudding, or silken tofu salad.In stir-fries or soups, it pairs well with pork. Taste it first—if it’s too salty, give it a quick rinse.

Stir-Fried Pork Slivers with Zhacai (can be made into soup and noodles)

Luobogan 萝卜干 & Caipu 菜脯

Luobogan (萝卜干), or preserved radish, is made by salting and sun- or wind-drying white daikon. You’ll find plain or spiced versions (like five-spiced and mala). It’s served as a side with rice or congee or eaten as a snack—often paired with alcohol. Southern Chinese regions like Hunan and Guangdong use luobogan in stir-fries and steamed dishes. You can also make luobogan at home from scratch.

One of the most famous varieties, caipu (菜脯), or chai poh, is widely used in Chaoshan (Teochew), Hakka, and Taiwan. It’s beige-colored, salty-sweet, crunchy, and sometimes aged for months—or decades—for deeper flavor. In Teochew cuisine, it’s added to congee (or served as a side to congee), soups, and fish dishes. The preserved radish omelet (chai poh neng菜脯煎蛋) and fried rice noodles (chai poh char kway teow 菜脯炒粿条) are two beloved Hakka dishes. Thai food writer Pailin includes chopped caipu in her Pad Thai, too—it adds a great crunch. Caipu also pairs well with seafood, like in this quick braised shrimp dish by writer Chen Yuhui (briefly fry the caipu and minced garlic, add water, then add shrimp, season with white pepper and salt)

How to Use Caipu:

It’s often quite salty straight from the package—chop and soak it in water for 5–10 minutes, then drain. Most recipes call for finely chopped pieces. If you can’t find caipu, non-spicy zhacai works as a substitute.

Omelet with Preserved Radish (I used the recipe from Phaidon China cookbook, similar see recipe)

Pad Thai (Hot Thai Kitchen)

Xuecai 雪菜

Xuěcài ("snow vegetable") is made by drying, salting, and fermenting a winter mustard green called xuelihong (雪里蕻). It’s popular in Jiangnan regions near Shanghai.

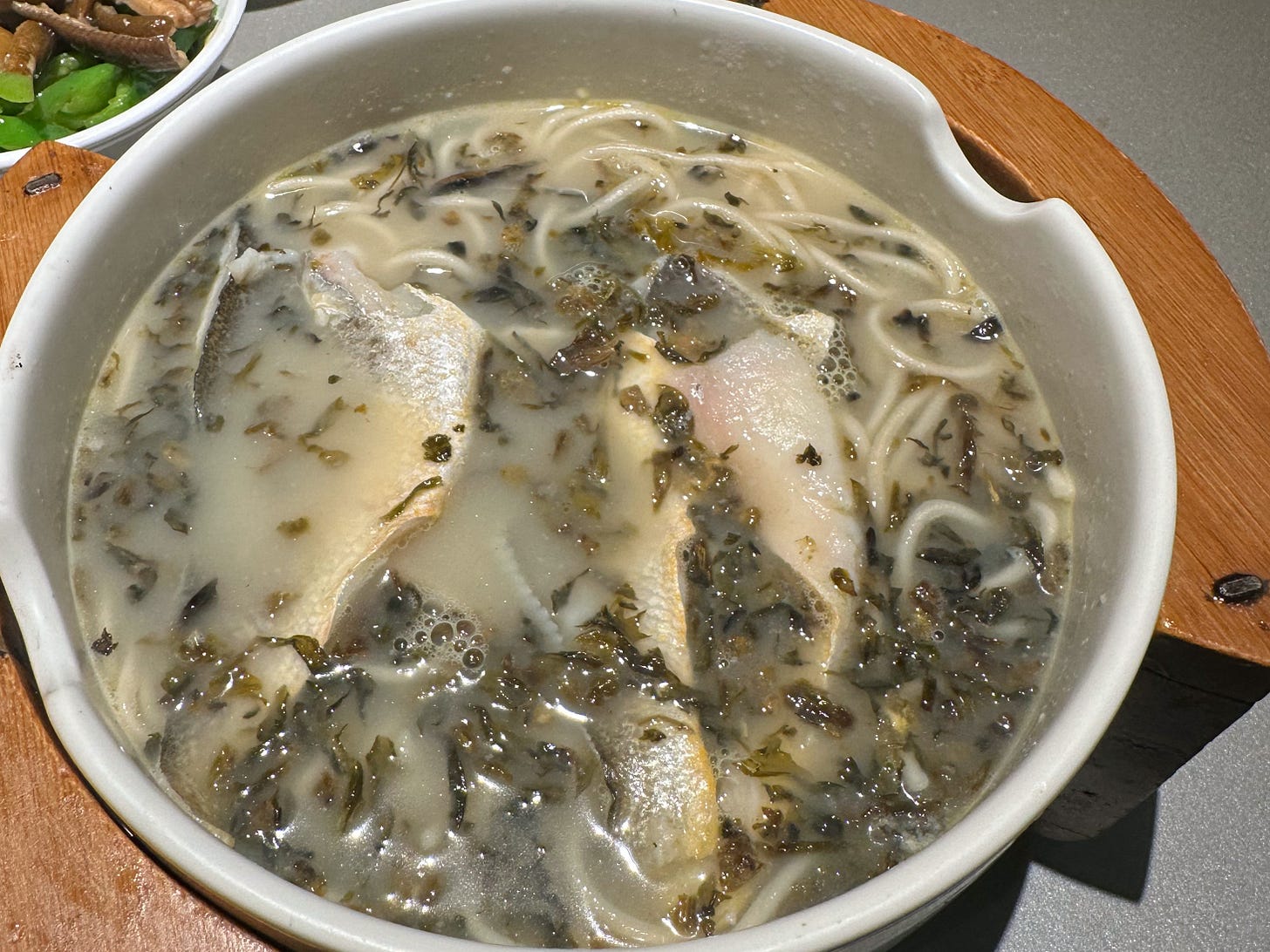

It’s also added to stir-fries, soups, and seafood dishes. I find it pairs especially well with mild ingredients like tofu, egg, and rice cakes—adding flavor without overpowering them. Compared to the yacai, it’s juicier and milder in savoriness, with a slightly sour taste. In Shanghai, a local favorite is yellow croaker noodle soup (黄鱼面) in a restaurant called Dingtele.

Xuecai is not as widely accessible as Yacai or Zhacai, but you’ll often find it in the same aisle in larger Chinese grocery stores, in bags or cans. Or make it yourself. I’ve used a version from the brand Yuquan.

How to Use Xuecai:

You can use it straight from the package—no rinsing needed. For stir-fries, cook it briefly with aromatics to bring out its flavor.You can add it to your fried rice (after adding the egg and rice); or quickly stir-fry with garlic and edamames (season with a little bit of soy sauce and salt). I recently add it to a fried egg soup with rice cake pieces and really enjoyed it (fry the beaten egg, add hot water, bring to a simmer. add rice cakes, xuecai and season with salt and sesame oil)!

Other Preserved Vegetables to Explore

There are hundreds of preserved vegetables across China, and I’ve only scratched the surface. A few more worth mentioning:

Meigancai 梅干菜

Méigāncàn, also called mei cai (梅菜) or written as 霉干菜, this dark brown fermented green is made from mustard greens or rape, salted, fermented and completely dried. Popular in Zhejiang, Hunan, and Fujian provinces, it’s often used in fatty pork dishes, pastries, and bao buns.

The dried Zhejiang version made in Shaoxing differs slightly from the sweeter, half-dried type made in Huizhou, Guangzhou. Most famously, it stars in the Hakka dish Meicai Kourou (梅菜扣肉)—steamed pork belly with meigancai.

To prepare meigancai, soak it in water until it's fully rehydrated, then rinse it thoroughly to remove any dust or impurities. For added depth of flavor, you can toast or lightly fry it before incorporating it into your dishes. Meigancai releases a uniquely rich, earthy aroma—especially when braised. Its fragrance can fill an entire room, adding a deep, savory note to your cooking. It pairs particularly well with braised pork belly (hongshaorou) or pork ribs, enhancing the dish with its unmistakable umami character.

Dongcai 冬菜

Dōngcài, or "winter vegetable," varies by region and is used for specific regional recipes. The most famous variety outside of China is probably the Tianjin preserved vegetable (天津冬菜), made from tender napa cabbage, similar to the Beijing variety.

In Sichuan—like my mom’s hometown Nanchong—it’s made from plants like tatsoi. I also tried a Yunan-style dongcai, made with mustard stems and greens, especially used for Yunnan-style rice noodles with tofu pudding. Sichuan and Yunan Dongcai are harder to find abroad. If a recipe calls for them, Xuecai is a decent substitute.

If you make it to the end, here’s an infographic to reveal all the preserved vegetables I showed at the beginning of the article!

In Sichuan, there used to be both salty Yacai from Nanxi (南溪), another district and sweet Yacai from Xufu (叙府). However, the latter eventually became synonymous with the product.

Also known as jingyong jiecai (茎用芥菜), yangjiaocai (羊角菜)

I'm speechless. I have never imagined that anyone would make such an effort to write a comprehensive overview on the intricacies of the humble Chinese preserved vegetables. I don't know where you get the picture of yellow croacker and xuecai soup. It looks exactly like what I had in Shanghai last spring.

Bravos!

I had this saved for while for me to read properly and so glad I finally did. Thank you!!! Chinese cuisine is so vast — at times can feel so intimidating with all its diversity. Your posts help me understand the intricacies of it so much better :)