When I last met my friend Ning from Taiyuan, Shanxi, she talked about a noodle dish called ti jian (剔尖): her mom would make a bowl of wet dough and swiftly scrape thin strips directly into the boiling water using a pair of chopsticks—a skill that she still marvels at today. Even though I've never tasted it, I imagined it to be something similar to German spätzle.

I’ve long been a fan of another Shanxi classic, knife-scraped noodles (dao xiao mian, 刀削面). Watching the chef holding a big, firm dough in front of the boiling pot, slicing strands straight into the giant steaming pot, is only one of the countless creative noodle making techniques in northern Chinese regions. They knead, bang, pull, slice, pinch, snip, and much more1. As a Southerner, noodle preparation techniques entered my repertoire only recently.

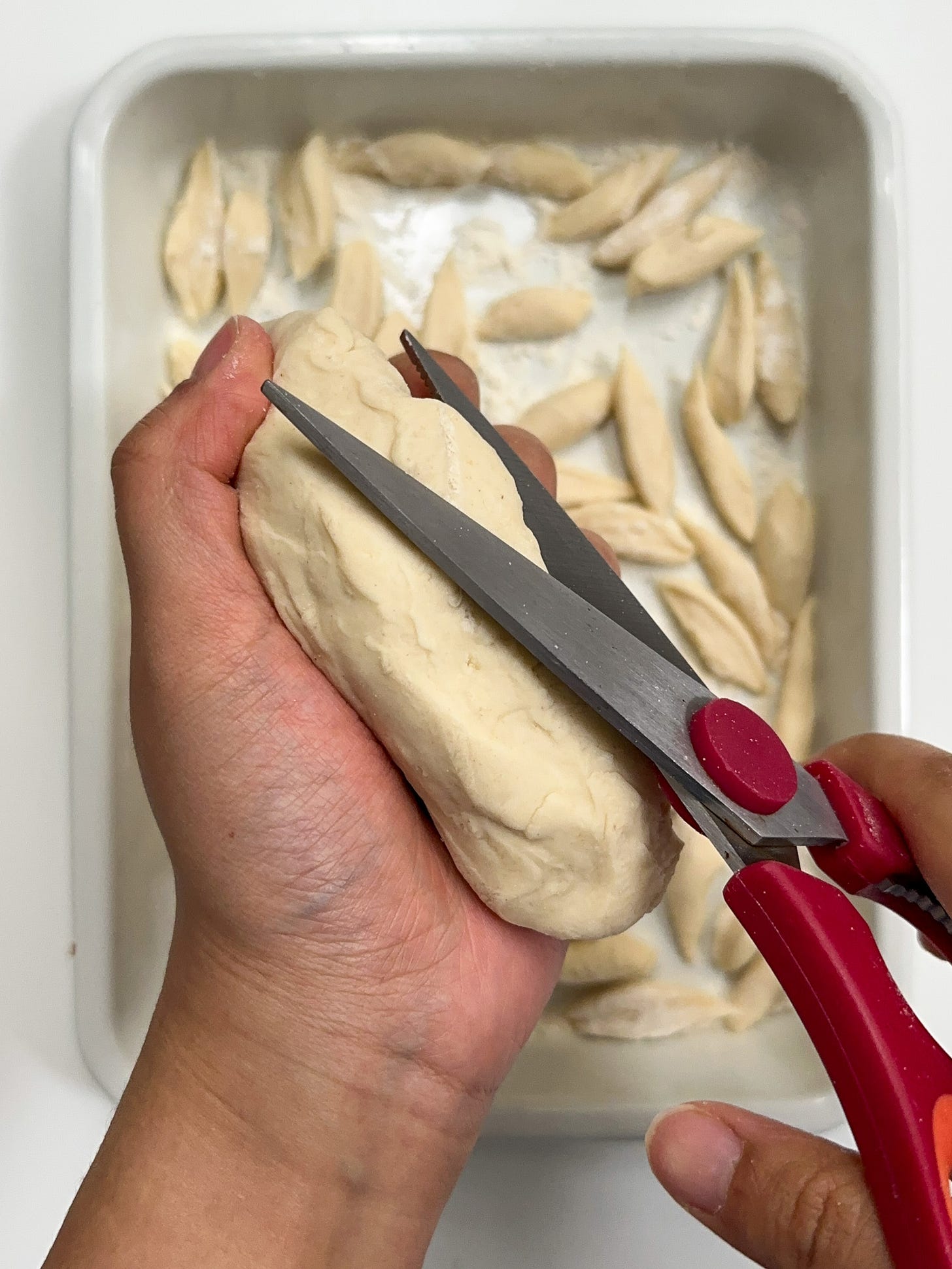

Scissor-cut noodles (jian dao mian, 剪刀面), for one, are extremely easy to make. To diverge from the usual tomato and egg or hot oil sauces, I tried a brown butter sauce for a nuttier and sweeter flavor (Thanks

for the butter influence!)—a departure from authenticity but an exciting twist. This creation oddly reminded me of another German dish, Schupfnudeln, also known as finger noodles.Dangerous territory. Nothing evokes more national pride than food like noodles or pasta on social media. After a shocking comment suggesting the Italian origin of sweet-water noodles, I started to read a bit about the origins of noodles in China.

A little history detour

The first written record of noodles appears in the Han Dynasty (circa 200 AD), referred to as “bing” (饼, translates to “dough”) 2. While there's controversy around a bowl of long millet noodles unearthed dating back four thousand years, noodles didn't gain prominence until the Song Dynasty, served with broth and toppings closer to what we know today. Long noodles and specialty noodles made with plum blossom or leaf juice, cold noodles cooled in well water appeared around this time.

Scissor-cut noodles, among other dough-pieces noodles like ti jian, are believed to have emerged around the Song and Yuan dynasties (8-14th century). The early form of irregular dough pieces is called 拔鱼 (ba yu, translates to “scraped fish-shaped dough”).

Pasta, the Italian equivalent, likely developed in parallel. The German Schupfnudeln, however, appeared as a soldier's food around the 17th century in the Thirty Years’ War.

It’s fascinating to read and uncover similarities in noodles as someone who resides and travels across cultures. Noodles are such a multifaceted concept, universal and regional, ancient and modern; as complicated as a historical dish or as simple as a quick dinner from a Chinese mom.

The recipe

Servings: 2-3

For the Dough

200g all-purpose flour

90g water (room temperature)

2 g salt

For the Sauce

1 tbsp vegetable oil

2 tbsp unsalted butter

2 cloves of garlic

2 scallions

2 tsp chili flakes

1 tsp Chinkiang vinegar

2 tsp sweet soy sauce or regular soy sauce

50g bean sprouts (optional)

Instructions

Mix flour and salt for the dough, then gradually add water until a smooth dough forms. Allow it to rest for 10-15 minutes.

Mince garlic and thinly slice the scallions, separating the white and green parts (the green part can be sliced into strips and kept in cold water for garnishing).

Once the dough is ready, boil a pot of water. Shape the dough into a thick log, dust with flour, and use clean kitchen scissors to snip 3 cm long pieces directly into the boiling water or onto a floured plate if it's your first time. Cook the noodles for approximately 5 minutes until they float. Cook the bean sprouts separately and drain both.

In another pan, heat vegetable oil and unsalted butter until the butter foams and turns brown. Lower the heat and add garlic, scallion whites, and chili flakes. Fry briefly until fragrant, then add the noodles and toss until coated with the sauce. Season with dark rice vinegar and sweet soy sauce. Serve with bean sprouts and scallion greens.

watch me make it here!

Tips for preparation

Like my other noodle and dumpling recipes, I typically start a dough using the 50% hydration rule (water weighing 50% of the flour, e.g., 100g flour, 50g water, and 1g salt). For this one I want to yield firmer dough to hold, so I reduce the water a bit. Adjust water quantity based on your flour's absorption.

To snip the noodles, rotate the dough to create small leaf-shaped pieces. Ensure the scissor tip is longer than the part you want to cut for clean edges.

If you’re making a bigger batch, dust with flour and freeze in a single layer for later use.

You could also serve this with a stir-fried tomato and egg topping (find my egg-fried noodles recipe here), and with a mince meat sauce, or any other noodle toppings you like.

In Fuchsia Dunlop’s new book Invitation to a Banquet, she dedicated a whole chapter to the history of noodles and her experience in Shanxi. One part mentioned that there are over 890 local flour-foods in Shanxi.

Growing up in The Netherlands as the son of a potato farmer, I ate pasta for the first time at 16. In Europe, pasta is considered to originate from Italy. Only later I found out the Italians got the idea from the East. For me, it’s hard to regard potato noodles as noodles. Potatoes are… not dough! 😁 And pasta is not made of potatoes. And noodles are always pasta. At least all the noodles I have ever encountered. But I guess it’s just how you name it.

Also it’s funny for me to see how ‘brown’ butter can be sort of new to others. For me it once was the other way around. In Northern Europe, or at least in The Netherlands, we used to bake everything in butter (or margarine). Not oil. Oil was something new to me that I only gradually started using the last 25 years. Now I use it for everything, except meat.