This is the third part of my travels through China (read Shanghai and Hangzhou), and perhaps the most fragrant.

Just 20 minutes by high-speed train from Hangzhou East, Shaoxing is best known in China as the hometown of literary giant Lu Xun and the birthplace of Shaoxing wine. Locals speak of its tradition of “three great vats” (三大缸): wine, soy sauce, and dye. Internationally, Shaoxing is one of the few places whose name lives on in the Chinese pantry, alongside Sichuan pepper and Chinkiang vinegar.

The region has been producing huangjiu (黄酒), yellow rice wine, for thousands of years. Its mild, humid climate and proximity to high-quality glutinous rice and the waters of Jianhu Lake make it an ideal brewing ground.

But Shaoxing is more than just yellow wine. Even a single day spent under the sweltering summer heat gave me some amazing culinary revelations. Most of them are rooted in fermentation, an ancient technique that remains very much alive.

We began on the northern outskirts, in Anchang (安昌古镇), an ancient water town where arched stone bridges span quiet canals. In the off-season, it was pleasantly tranquil. Anchang is famed for its soy-sauce-cured meats (酱货) and is home to a small soy sauce brewery. Along the canals, strings of sausages, fish, and poultry hang to dry. Stalls sell preserved vegetables in various hues, from dried preserved mustard, bamboo shoots, to daikon radish.

Renchang Brewery

Just past the entrance, we found a modest courtyard marked by four hand-painted characters: Ren Chang Jiang Yuan (仁昌酱园). The Renchang Brewery has been crafting soy-based condiments here since 1892 using traditional fermentation techniques.

Inside, rows of jars, some of which are from the Qing Dynasty, dot the 3,000-square-meter yard. Most of them hold soy sauce, others are filled with sweet flour sauce (甜面酱), and soybean paste (黄豆酱).

Their specialty is a double-fermented soy sauce known as “mother-and-son soy sauce” (母子酱油), which also serves as the foundation for the town’s cured meats. The process begins with cooked soybeans and wheat flour, left to develop mold (qu). This mixture is transferred to clay jars with salted water and left to ferment and sun-dry for six months—the resulting liquid is the “mother.” For the second fermentation, steamed wheat flour cakes (also inoculated with qu)1 are added—these are the “sons”. The two are fermented and sun-dried together for another six months, producing a soy sauce that is richer, deeper, slightly sweeter, and more mellow than the other supermarket varieties.

In the gift shop, I sampled two soy sauces and three types of furu (fermented tofu curd)—and was immediately hooked by the one infused with xiang zao (香糟), a liquid seasoning made from the lees of Shaoxing yellow wine (I will get to this amazing liquid soon!). This particular furu might be hard to find outside the region, though I’ve seen a Shaoxing brand called Xianheng (咸亨) that’s exported to Europe.

At the exit, we found a self-service fridge of soy sauce–flavored ice cream and a stall selling pastries filled with soy sauce and sweet flour paste. I skipped the ice cream, regrettably, but the pastries were superb: flaky, crisp, and perfectly balanced between sweet and savory. Naturally, a bottle of mother-and-son soy sauce and a jar of xiang zao furu came home with me to Berlin.

Mantou Made with Sweet Fermented Rice

A short walk led me to Xiao Dian Wang (孝店王), a family-run business known for its jiuniang (sweet fermented rice with grains) and mantou (steamed buns).

Inside the spacious courtyard, dozens of giant bamboo steaming baskets stood like installation art. However, it’s for practical reasons – I later read that drying the baskets thoroughly improves the buns’ texture, as the dry bamboo absorbs excess steam. On one side, a window sold fresh and vacuum-sealed goods; on the other, a team of women wrapped and cooked zongzi from scratch. The lively and indecipherable local dialect and the steam from the high-pressure cooker cooking zongzi rang through the air.

Mantou is a breakfast staple across China, but here, it comes with a twist: the dough is made using sweet fermented rice wine as the starter2. Instead of water and yeast, the lightly alcoholic brew is kneaded into the flour, along with some salt and sugar, giving the buns a naturally airy rise and subtle sweetness.

It was exceptional, probably one of the most memorable mantous I’ve had. The bun itself was feather-light, fluffy, tender, and slightly sweet, like biting into a warm cloud. The filling melted on the tongue: slow-braised pork belly infused with the deep, earthy aroma of preserved mustard and bamboo shoots (sungancai, 笋干菜).

I went back for a zongzi—sticky rice wrapped in bamboo leaves and filled with the same pork filling. Then, one final trip to the counter for a bag of meigancai to take home, hoping to preserve just a little of that flavor magic.

In Shaoxing, Jiuniang is especially popular. Later that day, I stumbled upon a modern rice wine café where the classic was reimagined in playful ways: stirred into coffee, blended with fruit, or made into ice cream molded into the character for “Shaoxing” (绍兴). Sleek packaging and modern design are clearly targeting younger eaters. As I’d already advocated in Bingfen, jiu niang makes a natural fit for desserts: mellow and subtly boozy, it works beautifully in just about anything sweet.

The region is rich with glutinous rice–based treats, and one of them is Yin Gao (印糕),—a delicate, steamed, mochi-like pastry stamped with patterns and filled with fragrant osmanthus and sweet red bean paste.

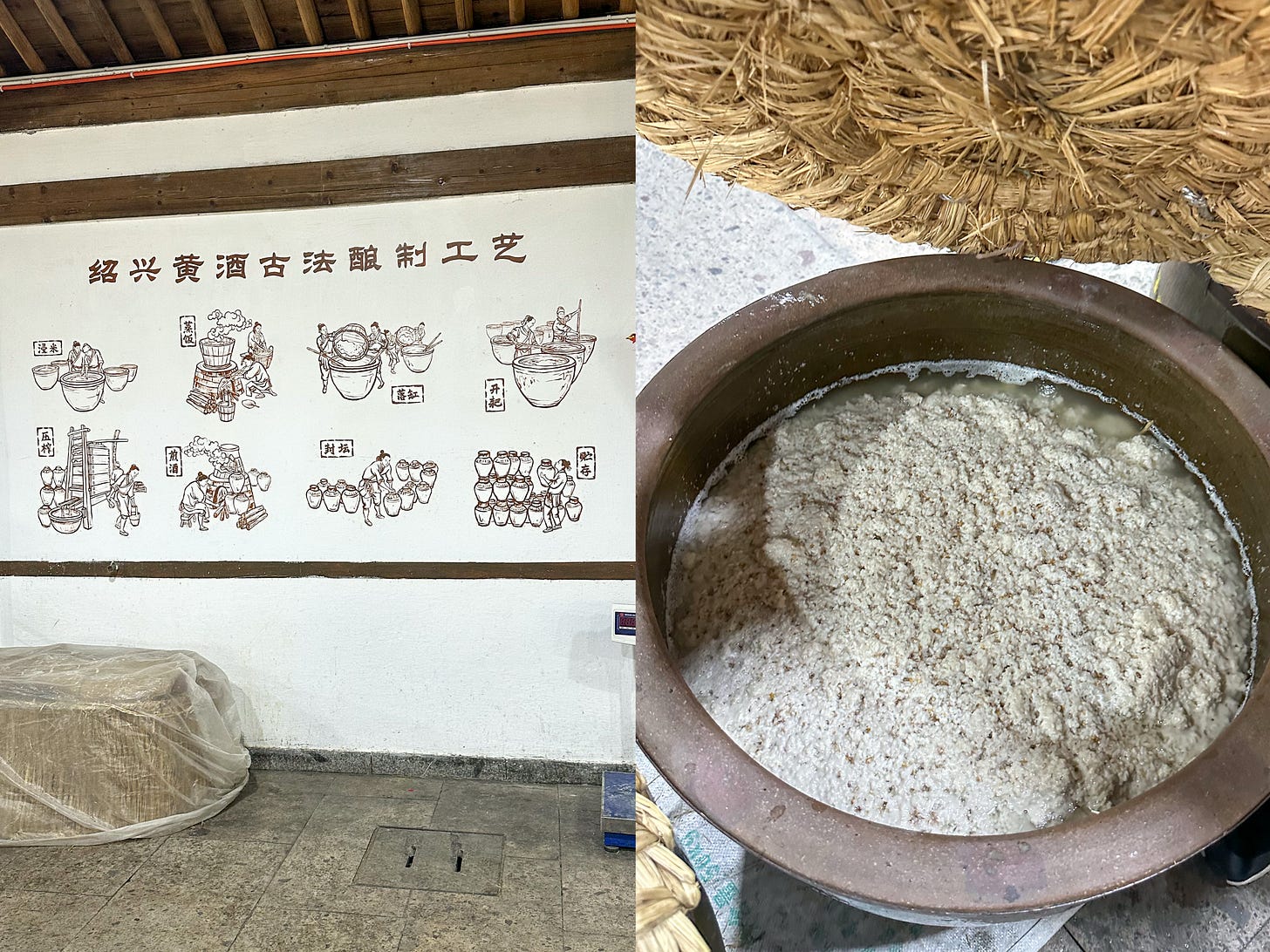

Shaoxing Yellow Wine Museum

The Chinese Yellow Wine Museum (中国黄酒博物馆) sits near the heart of Shaoxing’s old town, marked by a few ancient wine vessels at its entrance. While most people outside China might recognize Shaoxing wine primarily as a cooking ingredient, here in its birthplace, yellow wine is first and foremost a beverage, and that’s exactly what the museum celebrates.

Funded in part by Guyue Longshan (古越龙山), one of the region’s most prominent producers, the museum traces the story of wine brewing through the dynasties. Exhibits highlight fermentation techniques, drinking customs, and the ritual culture surrounding huangjiu.

Shaoxing wine is traditionally made from steamed glutinous rice, a rice-based wine starter (jiu qu 酒曲), wheat koji (mai qu 麦曲), and water from the local Jianhu lakes. The mixture is first fermented in big jars and stirred daily. When wine comes out, it’s transferred to smaller jars to ferment further for months. Then the wine is pressed, heated, and aged for years.

The variety most familiar abroad is jiafan jiu (加饭酒) or huadiao (花雕), a semi-dry wine with extra rice added for richness. It’s also the most widely exported style.

Just like any wine, the spectrum of Shaoxing wines is broad. There’s yuanhong (元红, dry), shanniang (善酿, semi-sweet), and xiangxue (香雪, sweet), offering their distinctive profile.

Cooking was mentioned in passing. One panel noted that Shaoxing wine is prized for its ability to “remove gaminess, eliminate fishy odors, and add aroma and complexity.” A nearby chart caught my eye: researchers have identified 718 flavor compounds in Shaoxing wine, including four basic tastes except salty (sweet, sour, bitter, and umami), stone fruits like peach and nectarine, and sweet elements like caramel and honey. No wonder this wine adds such depth to both the glass and the pan.

The Stink

As we approached one of Shaoxing’s tourist streets, one scent became impossible to ignore: the pungent, unmistakable smell of stinky tofu (chou doufu, 臭豆腐). Every 50 meters, a stand advertised its product as a "heritage recipe." I chose one with a modest queue.

Unlike the dark, charcoal-hued version from Hunan, which is marinated in the liquid with fermented black beans (douchi), Shaoxing’s stinky tofu is pale beige to yellow. Its distinct aroma comes from soaking the tofu in a brine made from fermented amaranth stems (霉苋菜梗), a local obsession. This pungent liquid is also used to flavor other ingredients, such as gourd and winter melon, forming the city’s infamous trifecta: Shaoxing’s Three Stinks (绍兴三臭): amaranth stems, tofu, and winter melon (some also include the tofu skin, qianzhang).

The vendor explained that the tofu must be firm and gypsum-set. To my surprise, the cubes are soaked for only one night, far shorter than I would have guessed for something with such an intense smell. Each piece is fried to order until golden and crisp, then served with chili sauce and sweet flour sauce. The result is a beautifully crisp exterior and a softer interior thanks to the fermentation. Delicious in texture, though admittedly, the funky smell is not for the faint of nose, even I found it challenging at first.

Shaoxing is inevitably a bit too touristy for my taste. However, what I love about it is how the magic of transformation happens again and again—food doesn’t just change once, but evolves through layers. Fermented vegetable brine flavors tofu. Glutinous rice becomes wine; the wine slips into mantou dough, enriches dishes, and even its byproducts flavor cold plates and season fermented tofu. Soybeans become soy sauce, which in turn seasons cured meats and countless other creations. In Shaoxing, fermentation is a cycle of reinvention woven into every bite.

Before catching our train at dawn, we squeezed in one last meal at a humble diner serving home-style dishes. We returned to the braised ribs with meigancai, tried a daily special of stir-fried goose stomach, and warmed ourselves with a milky tofu soup rich with fish head.

As the train sped back toward Hangzhou, golden light blurred the borders of the two cities. Shaoxing had become a place I’ll be thinking about and cooking from.

This video shows how the flour cake is made and kneaded

This documentary clip shows how Zhejiang people make jiu niang mantou

Fascinating! Ancient towns have so much to offer in terms of history and food. I'm putting this on the list for when I return!

I love fermented food, but my selection has been nothing as impressive as what you saw. Thanks for sharing🙏🏽